Have you ever wondered why St Mary’s Tower, you know the building with pointy roof at the edge of Museum Gardens, looks as though some great monster has taken a bite out of it?

Well, to answer that question, allow me to take you back to the world of 17th Century Britain — and the English Civil War.

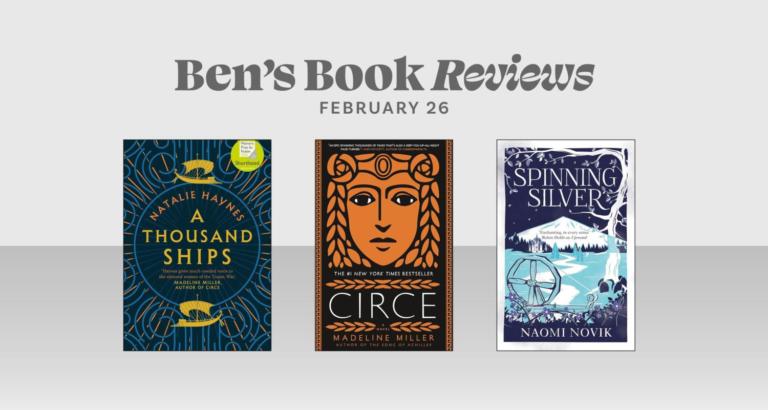

Artist’s impression of St Mary’s Tower and Bootham Bar, c.1850s

At the time, York was considered by all to be the ‘capital’ of the north of England, and by most, to be the nation’s second city after London, (we think this is still the case by the way!) so when civil war broke out between Royalists (those loyal to the King) and Parliamentarians (those wanting to give Parliament more power) it was only a matter of time until York saw action.

The worst onslaught of this occurred in the spring of 1644, in what is now remembered as ‘The Siege of York.’

Despite being a royalist stronghold, York had been relatively safe from Parliamentarian aggression for the first couple of years of the war. This was thanks to the Earl of Newcastle and his army from the northernmost counties, which had been stationed nearby. The temporary sense of safety enjoyed by York’s residents was not to last though.

In early 1644 the Parliamentarians signed a treaty with the “Scottish Covenanters”, leading to an invasion across the border by the Scottish Earl of Leven.

This attracted the attention of the Earl of Newcastle, who marched up north to face the threat — leaving York exposed and vulnerable. The Earl left just over 3,000 men behind to defend York, from a growingly emboldened Parliamentarian army stationed in Cheshire.

The two forces (the army left in York and the Cheshire Parliamentarians) first met at a skirmish in Selby on April the 11th, where the Governor of York was captured, and the town quickly overrun.

Over 1,600 Royalist soldiers were taken prisoner, leaving York all but undefended.

On hearing the news, the Earl of Newcastle immediately understood the threat posed to York and quickly turned tail, and returned to York by the 19th of April. He was followed south by the Scottish army though, who joined forces with the Parliamentarians who were already beginning siege preparations.

By the 22nd of April, York was surrounded by the Scots from the West and a Lord Fairfax-led Parliamentarian army from the East. Sensing victory was unlikely, the Earl of Newcastle sent the majority of his cavalry out of the city to join larger Royalist forces elsewhere. A garrison

of just 800 horse soldiers and 5,000 footmen remained.

By the start of May, the Parliamentarians had been joined by a third force, led by the Earl of Manchester, who was fresh from routing another Royalist stronghold in Lincoln. So, it wasn’t looking great for the, already pretty hungry, people of York.

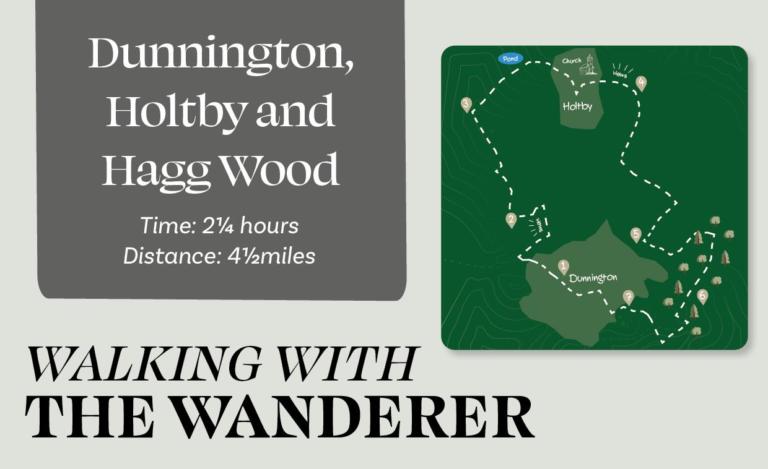

York’s defences consisted of an inner ring formed around the mediaeval city walls and an outer ring of several “sconces” (small, detached earthwork forts, each with a garrison of infantry cannons) at a distance from the walls.

The besieging Parliamentarians began by attempting to overcome these sconces, to tighten their grip around the city. The trickiest of these to overcome was a sconce on The Mount. Half-a-mile from Micklegate Bar and now home to many of our favourite city centre hotels, in the 17th Century The Mount was a very different proposition. It was a key strategic position with a very wide range of cannon fire, so try as the Scots might, they couldn’t get close enough to overpower the Royalist guns.

So, 400 words later after I drew you in with the promise of a story about St Mary’s Tower, you’re probably all wondering what any of this has to do it. But please bear with me for a couple more lines, as I promise, we’re getting there!

On the morning of 16 June 1644 — the Parliamentarians switched strategy. Forgetting all about The Mount, the Earl of Manchester (remember him? The guy who just arrived from Lincoln) set about at attacking the city from the other side. He put guns on Lamel Hill and battered the hell out of Walmgate Bar, then put an explosive mine under the Walmgate Barbican!

All at the same time, the crafty Earl also placed another explosive mine underneath St Mary’s Tower. The Tower was completely demolished — allowing for a regiment of Parliamentary troops to breach the wall and temporarily enter the city. What they didn’t realise however, was that a group of York’s Royalist soldiers had been hiding around the corner at Postern Gate (near the Wetherspoons!)

The Royalists snuck around the back of the Parliamentarians, trapped them, and sealed the breach in the wall.

The Tower would not be so lucky though. The mine succeeded in shattering its foundations and the walls were left a crumbled and dilapidated mess. While the tower was later rebuilt using some original materials that preserved its octagonal interior, albeit with thinner exterior walls, if you look closely though you’ll notice the reconstructed bricks are a few tones darker and follow an irregular curve — making it look as though a chunk is missing.

Today the Tower is home to the York Singing Academy, where its tall octagonal shape provides the perfect acoustic environment for new generations of York’s signers to refine their sounds.

And what of the siege? Well, after sealing the breach at St Mary’s Tower, the people of York were relieved by an arriving army led by the Royalist Prince Rupert of the Rhine.

There wasn’t much to celebrate though. The next day the northern Royalist Army (made up of the Earl of Newcastle and Prince Rupert’s forces) were soundly defeated by the Parliamentarians at The Battle of Marston Moor. The battle essentially ended all northern support for the King’s Royalist cause, setting the stage for all-out Parliamentarian victory in 1646.

Add a comment