Join us as we journey back in time. No pushing.

Ever turned off Micklegate onto Trinity Lane and wondered what the deal is with that curious timber frame building you pass on your right? Well… (tee hee), that would be Jacob’s Well, a medieval structure with a varied past. But who was Jacob, where’s this well, and why is it still here at all in a part of the city that has seen so much redevelopment lately? We found out.

The building we today know as Jacob’s Well owes its existence to neighbouring Holy Trinity Church. As we’ve written about in this column previously, Holy Trinity was once an important Benedictine priory, dominating the land along Micklegate from Trinity Lane to Priory Street from 1100CE. Jacob’s Well, which was built late in the priory’s life in around 1474, was constructed by Alderman Thomas Nelson to house a chantry priest; a guy who was paid to pray for the Nelson family three times each day in the priory. Cushty job, we think.

Horrid Henry

Horrid Henry

However, that investment by the Nelsons came to an end in 1535 when, thanks to Henry VIII, the priory was dissolved and the parish church of Holy Trinity was established. The chantry priests were finally booted out in 1547, and two years later Jacob’s Well was purchased by Isabel Warde, the final Prioress of Clementhorpe Nunnery – who had also recently found herself homeless. In 1566, three years before her death, Isabel gifted the building back to Holy Trinity Church, on the condition that she could live there for the rest of her natural life. Her annual rent was recorded, quite poetically, as one red rose delivered on midsummer’s day. Why not try that with your landlord?

Following her death the building became the rectory of the vicar of Holy Trinity, which we can imagine was quite handy, what with the church being just a (short) stone’s throw away. In 1633 Henry Rogers is recorded as living there, and he was most probably responsible for many of the building’s post-medieval alterations. He inserted the floor, splitting the building into a two-story house, built a spiral staircase to get up there, and created new windows overlooking the church. However, he was also responsible for ending the building’s association with the church yet again, as he built a new, larger rectory next door – where today the current church rectory stands.

Whose round is it?

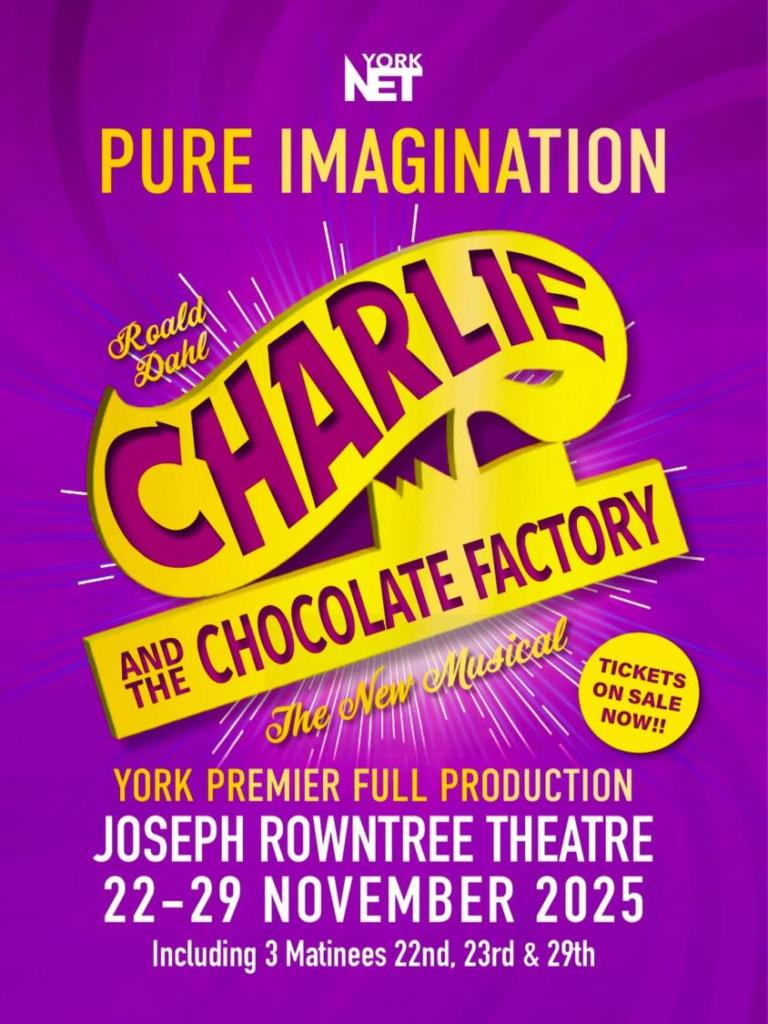

In stark contrast to its original intent, the building next, in 1749, became a pub. Cheers! Leased by Elisabeth Knapton, it is at this time that the name Jacob’s Well was first used; coming from the Old Testament story of how Jacob met Rachel at a well when watering his animals, and fell in love with her. We’re not sure if this was a sly way of suggesting that patrons might “find love” while visiting, but pretty much every building in York has at some point been a brothel, so…

Anyway, Elisabeth held the lease until 1790 when it was taken over by Roger Glover and John Furnish who were recorded as ‘coach masters’, with stables across the street. In 1815 the building was enlarged with the addition of a brick upper story – sitting right on top of the medieval wooden frame. Although the extra space probably served the guests well, it definitely wasn’t a great architectural decision, as you’ll discover.

Well I never…

In 1903 the license for the pub was transferred to another place in Micklegate and Jacob’s Well once again found itself in the possession of the church. In 1905 remodelling work was carried out, resulting in a grand new staircase leading to the upper levels, and reconstruction of the door using carved wooden brackets rescued from the historic Wheatsheaf pub which once stood on Davygate. From that point onwards the building was used quite as it is today; as a community space that served Holy Trinity church (it’s okay though – there were plenty of other pubs along Micklegate, so we hear).

But… by 1990 the building was in dire need of attention. The vibration from passing traffic was causing damage to the original timber frame, and that brick upper story was in danger of collapsing. It was leaning out over Trinity Lane, and the ceiling below was severely sagging. In a rare move, part of the Grade 1 listed building was demolished – with the approval of English Heritage – and the upper story was removed and a new roof installed, bringing Jacob’s Well back to it’s pre-1815 height. Toilets were also installed at this point, with the ladies’ taking the place once occupied by the original spiral staircase to the upper floor.

Changing faces

So in many ways, Jacob’s Well is a pretty typical, yet very interesting, example of an old York building: built for one purpose, but having had many uses since. You can hire it these days for a function (it costs more than one red rose, though), and a wander around is well worth it if you get the chance.

Add a comment